Nimes in the Occitanie region of southern France is a wonderful and ancient city with a plethora of Roman remains including a virtually complete amphitheatre and temple (La Maison Carre), which frankly make most of the Roman remains in England look like random heaps of rubble and barely worth bothering about.

History notwithstanding, tonight we are in Nimes for the match between Olympique Nimes and AJ Auxerre, two football clubs that have in the past both played at the top level of French football, Auxerre having even won the Ligue 1 title. Today however, both are in the under-hyped Ligue 2, the second of France’s two professional leagues. Despite France’s reputation for haute cuisine, Ligue 2 is sponsored by Domino’s Pizza.

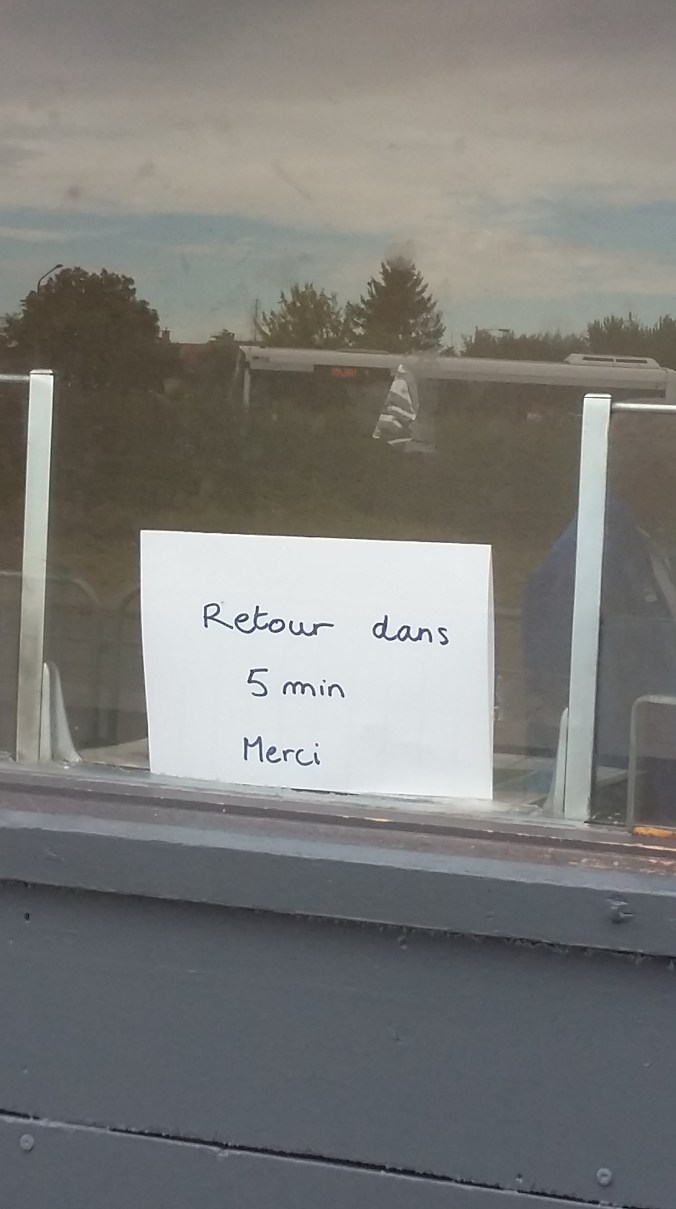

We bought our tickets at the Stade des Costières stadium earlier in the day to avoid any queue, although we did have to wait a short while because the sign in the window of the guichet read ‘back in five minutes’. Tickets for the main stand cost 14 euros, whilst those for the identical stand opposite are 9 euros and a ticket behind the goal costs 4 euros. We buy 9 euro tickets in the Tribune Sud (South stand). There are acres of free car parking all around the Stade des Costières and arriving a little more than an hour before kick-off it’s easy to park up near the exit for a quick getaway after the match. Nevertheless, there are plenty of people here already, buying tickets, standing about, socialising and heading to bars for a pre-match aperitif.

at the Stade des Costières stadium earlier in the day to avoid any queue, although we did have to wait a short while because the sign in the window of the guichet read ‘back in five minutes’. Tickets for the main stand cost 14 euros, whilst those for the identical stand opposite are 9 euros and a ticket behind the goal costs 4 euros. We buy 9 euro tickets in the Tribune Sud (South stand). There are acres of free car parking all around the Stade des Costières and arriving a little more than an hour before kick-off it’s easy to park up near the exit for a quick getaway after the match. Nevertheless, there are plenty of people here already, buying tickets, standing about, socialising and heading to bars for a pre-match aperitif.

The stadium itself isn’t open yet, but we file in a minute or two after seven o’clock and the now standard frisking and bag inspection. The Stade des Costières was opened in 1990 and designed by Vittorio Gregotti and Marc Chausse; Gregotti was also architect of the Stadio Communale Luigi Ferraris in Genoa, one of the venues for the 1990 World Cup. Although the stadium does now look a little run down in places, it is nevertheless a fine building and a great place to watch football. There are two broad sweeps of grey seating on either side with roofs suspended from exposed steelwork.

The ends are open and each corner of the ground is a white concrete block containing the accesses, buvettes and toilets and on the main-stand side, club offices. Inside these blocks the ramps and staircases read more like an art gallery than a football stadium and from the ramps there are views across the seats through sculpted openings. The stands behind the goals with their bench seats and classical-style structures at the back, which whilst looking a bit naff somehow also look alright in this context, make me think of the arène (amphitheatre) in the centre of town; I hear a far of voice of a hawker “ Otter lips, Badger spleen!”.

The sun is setting spectacularly behind the Tribune Ouest casting soft shadows on the white concrete of the Stade, the clouds that have made it a grey day are dispersing, the floodlights are on and the teams are warming up. There is a wonderful air of expectancy and relaxed sociability as the Stade fills up and people throng by the pitch and on the broad concourse behind the seats. Some men drink beer; some stuff their faces with baguettes from the buvette, whilst other have brought food from home, carefully wrapped in tin foil. Bags of a locally produced brand of ‘artisan’ potato crisp are much in evidence.  Nimes’ crocodile mascot does his rounds as people, mostly children, pose for selfies with him; I am very tempted but my wife gives me a look. With the teams’ and Ligue 2 banners on the pitch a man with a radio mike gees up the crowd as the teams enter from the corner of the ground. There are ultras both behind the goal and beside the pitch, waving flags, standing clapping and jumping about. The chant is “Allez-Nimois, Allez-Nimois”. I join in. Why the hell isn’t it like this at Ipswich? The crowd is less than half the size of that at Portman Road (6,771 tonight) but three, four, five, a hundred times more involved. There are just a handful of stewards in the stand; I don’t feel like I am here to be policed, but to enjoy the match.

Nimes’ crocodile mascot does his rounds as people, mostly children, pose for selfies with him; I am very tempted but my wife gives me a look. With the teams’ and Ligue 2 banners on the pitch a man with a radio mike gees up the crowd as the teams enter from the corner of the ground. There are ultras both behind the goal and beside the pitch, waving flags, standing clapping and jumping about. The chant is “Allez-Nimois, Allez-Nimois”. I join in. Why the hell isn’t it like this at Ipswich? The crowd is less than half the size of that at Portman Road (6,771 tonight) but three, four, five, a hundred times more involved. There are just a handful of stewards in the stand; I don’t feel like I am here to be policed, but to enjoy the match.

The game begins; Nimes kicking off towards the Tribune Est in their red shirts with white shorts and red socks, Auxerre in white shirts with blue shorts and white socks. After only eight minutes a poor punch by the Nimes ‘keeper Marillat requires a second punch but the effort is too much and he falls to the ground clutching his knee. Both the physio and club doctor attend to him and Marillat carries on, but for less than fifteen minutes before he has to be substituted. Nimes lose a second player to injury in Valdivia who had previously been fouled by Auxerre’s Phillipoteaux, who is the first player to be cautioned by referee Monsieur Aurelien Petit. How witty of the LFP to send a referee to Nimes who shares his first name with a Roman Emperor. Nimes are attacking more than Auxerre or in greater numbers, but are creating no more or better chances. It doesn’t look much like anyone will score.

In the stand a large man in a white polo shirt, which barely conceals the presence of flabby breasts, is exhorting his fellow supporters with the use of a megaphone. At first he is ignored but he doesn’t give up and begins to sing softly, but then with increasing strength before he signals to a drummer besides him who breaks out a rhythm and people to start to jump and clap and sing and have a helluva of a time, before going quiet and the whole performance is repeated. It’s like a flash-mob version of Bjork’s “It’s oh so quiet” in which the main lyrics are “Allez-Nimois”. It’s a lot of fun.

Four minutes of added time for injuries precede half-time in which there is a shoot-out between two teams of what are probably under-tens. The goalkeepers are somewhat dwarfed by the goals and the shoot-out takes a long time because the boys have to run from the half way line; there is one girl in the two teams and her goal receives the biggest cheer. How might radical feminists view that? As positive discrimination or as patronising? Discuss. Meanwhile an advertisement hoarding encourages spectators to travel to the match on the “Trambus”, which is really just an articulated bus with fared in wheels and a dedicated bus lane, but it’s good to see the football club and local authority combining to promote public transport in spite of all the free parking spaces.

Within thirty seconds of the re-start Nimes have a corner after a good dribble, but poor shot from Thioub. From the corner the ball is partly cleared and Auxerre’s wonderfully named 36 year old Guadeloupian, Mickael Tacalfred tries to clear the ball further but collides with Nimes’ Bozok and Monsieur Aurelien Petit awards a penalty and instantly brandishes his red card in the direction of Tacalfred for dangerous play (a high boot or “coup de pied haut”). Both the award of a penalty and the sending off seem somewhat harsh. The game is delayed as the matter is discussed at length by the Auxerrois but eventually Savannier puts Nimes ahead. “B-u-u-u-u-u-t! ” shouts the announcer through the public address system before calling out the goal-scorer’s first name to which the crowd give his surname in response.

More drama ensues as Auxerre’s Arcus collides with the replacement Nimes ‘keeper Sourzac. Arcus had already been booked in the first half so quickly leaves the scene of the incident as Sourzac stays down clutching his chest, but is of course okay really and later he easily saves Auxerre’s only shot on target.

Sixty-three minutes have passed and now there is a free-kick to Nimes and a booking for Auxerre’s Yattara who had been whining all game. Nimes’ Moroccan forward Alioui does a little shuffle, as if to take a rugby-style kick, before running up and arrowing a shot over the defensive wall and into the top left hand corner of the Auxerre goal. A brilliant shot which predictably is met with a great deal of noise and excitement, all of it justified. At the front of the stand, fans pogo whilst chanting an extract from Bizet’s Carmen.

Nimes are exultant, Auxerre vanquished but it isn’t over yet. Alioui keels over to earn another free kick to Nimes in roughly the same place as he took the first. Whilst he repeats the earlier performance with a missile of a shot that Kim Jong-un might covet, Auxerre’s ‘keeper Boucher dives to save the shot, only for the Nimes captain Briançon to score from the rebound. Joy abounds amongst les Nimois.

The final fifteen minutes sees the best football of the match as both teams relax, knowing the inevitable result and not wanting to add to the tally of yellow and red cards. Nimes ultimately deserve their win, but have had a big helping hand from the referee Monsieur Aurelien Petit along the way. Nevertheless, overall it’s been a blast; I have had a lot of fun on a fine evening, in a beautiful stadium in a fine city with excellent supporters, even if the France Football correspondent later only marks the match as 8 out of 20. Allez Nimois!

to see the tie with Clermontaise, who are from the town of Clermont l’Herault, some thirty kilometres to the north west.

to see the tie with Clermontaise, who are from the town of Clermont l’Herault, some thirty kilometres to the north west.

It looks like the original roof has been replaced with new metal sheeting on another metal frame, which obscures the row of the pitch from the front row of seats. We enter the stadium through a wide opening in the back wall and find ourselves in the players tunnel; it’s an entrance that is closed soon afterwards, but it’s not quite two -thirty yet and the game doesn’t kick off until three. A wonky sign points roughly in the direction of the buvette,

It looks like the original roof has been replaced with new metal sheeting on another metal frame, which obscures the row of the pitch from the front row of seats. We enter the stadium through a wide opening in the back wall and find ourselves in the players tunnel; it’s an entrance that is closed soon afterwards, but it’s not quite two -thirty yet and the game doesn’t kick off until three. A wonky sign points roughly in the direction of the buvette, which is a portakabin style structure with a counter even more wonky than the sign. To the other side of the stand is a dark room with high-up shelves of trophies on two walls and a bar counter;

which is a portakabin style structure with a counter even more wonky than the sign. To the other side of the stand is a dark room with high-up shelves of trophies on two walls and a bar counter;

and the teams line up on the pitch. Balaruc wear an unattractive all-black kit with green trim, which displays no team badge or sponsor’s names. Clermontaise and Balaruc are in the same regional league (Poule A of the Languedoc-Rousillon section of the Occitanie region’s Division Honneur 2 – the seventh level of French football), but Clermontaise look much smarter and ‘professional’ in their all blue kit with badge. The McDonald’s golden arch logo is on the Clermontaise shorts; they can’t have read the poster on the table in the trophy room.

and the teams line up on the pitch. Balaruc wear an unattractive all-black kit with green trim, which displays no team badge or sponsor’s names. Clermontaise and Balaruc are in the same regional league (Poule A of the Languedoc-Rousillon section of the Occitanie region’s Division Honneur 2 – the seventh level of French football), but Clermontaise look much smarter and ‘professional’ in their all blue kit with badge. The McDonald’s golden arch logo is on the Clermontaise shorts; they can’t have read the poster on the table in the trophy room. at the Mediterranean end of the ground. A bloke in a t-shirt and trakkie bottoms is called on to sort them out and once he has done so the game carries on. Early on Clermontaise look the better team, but it might just be because they’re wearing a nicer kit. Just before twenty past three it looks like they have scored, but I can’t tell if it was offside or the shot was missed. There are flattened practice goals either side of the real one and from my rock it’s hard to tell which is which.

at the Mediterranean end of the ground. A bloke in a t-shirt and trakkie bottoms is called on to sort them out and once he has done so the game carries on. Early on Clermontaise look the better team, but it might just be because they’re wearing a nicer kit. Just before twenty past three it looks like they have scored, but I can’t tell if it was offside or the shot was missed. There are flattened practice goals either side of the real one and from my rock it’s hard to tell which is which. There are a number of people, mostly men in their sixties and seventies, sat at windows and balconies looking down on the game. I envy them their home comforts, it has to be better than perching like a lizard on a rock in the sun. Dissatisfied with my view sat on the rock, I watch the remainder of the first half standing up.

There are a number of people, mostly men in their sixties and seventies, sat at windows and balconies looking down on the game. I envy them their home comforts, it has to be better than perching like a lizard on a rock in the sun. Dissatisfied with my view sat on the rock, I watch the remainder of the first half standing up. It proves to be a good choice and our enjoyment of the second half is much increased by our new location, which is shaded, out of the wind and high enough to see over the fence, with the added bonus of atmosphere as the stand is full; spectating nirvana.

It proves to be a good choice and our enjoyment of the second half is much increased by our new location, which is shaded, out of the wind and high enough to see over the fence, with the added bonus of atmosphere as the stand is full; spectating nirvana. Monsieur Gerard Blanchet busy in front of us. Clermontaise’s number twelve confirms his presence by boldly attempting a shot from a thirty metre free kick; of course he misses, but not embarrassingly so. The Balaruc bookings continue and five blatantly kicks the Clermontaise twelve as he dribbles past him and three knocks over his opposite number as they run side by side. All afternoon tbere is a pleasing symmetry with many of the fouls and bookings as players with the same shirt number go for each other.

Monsieur Gerard Blanchet busy in front of us. Clermontaise’s number twelve confirms his presence by boldly attempting a shot from a thirty metre free kick; of course he misses, but not embarrassingly so. The Balaruc bookings continue and five blatantly kicks the Clermontaise twelve as he dribbles past him and three knocks over his opposite number as they run side by side. All afternoon tbere is a pleasing symmetry with many of the fouls and bookings as players with the same shirt number go for each other. near the Atlantic coast, some 380 kilometres away by road; they have won one and lost two of their four games so far. Kick-off is at six pm and we arrive about a half an hour beforehand, parking in the spacious gravel topped car park at the side of the Stade Louis Michel, although other spectators prefer to park in the road outside. Entry to the stadium costs €6 and we buy our tickets from the aptly porthole-shaped guichets

near the Atlantic coast, some 380 kilometres away by road; they have won one and lost two of their four games so far. Kick-off is at six pm and we arrive about a half an hour beforehand, parking in the spacious gravel topped car park at the side of the Stade Louis Michel, although other spectators prefer to park in the road outside. Entry to the stadium costs €6 and we buy our tickets from the aptly porthole-shaped guichets  outside the one gate into the ground. Just inside the gate a cardboard box propped on a chair provides a supply of the free eight-page, A4 sized programme ‘La Journal des Verts et Blancs’. Also today there is a separate team photo and fixture list on offer.

outside the one gate into the ground. Just inside the gate a cardboard box propped on a chair provides a supply of the free eight-page, A4 sized programme ‘La Journal des Verts et Blancs’. Also today there is a separate team photo and fixture list on offer. the brutal angular concrete of the main stand, the Tribune Presidentielle, could be from the 1960’s or 1970’s, channeling the inspiration perhaps of Auguste Perret or even Le Corbusier. The concrete panels on the back of the stand are lightly decorated and sit above wide windows; a pair of curving staircases run up to the first floor around the main entrance,

the brutal angular concrete of the main stand, the Tribune Presidentielle, could be from the 1960’s or 1970’s, channeling the inspiration perhaps of Auguste Perret or even Le Corbusier. The concrete panels on the back of the stand are lightly decorated and sit above wide windows; a pair of curving staircases run up to the first floor around the main entrance,  above which is a fret-cut dolphin, the symbol of the town and the club. The stand runs perhaps half the length of the pitch either side of the halfway line and holds about twelve hundred spectators, as well as club offices and changing rooms. Opposite the main stand a large bank of open,

above which is a fret-cut dolphin, the symbol of the town and the club. The stand runs perhaps half the length of the pitch either side of the halfway line and holds about twelve hundred spectators, as well as club offices and changing rooms. Opposite the main stand a large bank of open,  ‘temporary’ seating runs the length of the pitch, it is built up on an intricate lattice

‘temporary’ seating runs the length of the pitch, it is built up on an intricate lattice  of steel supports. Behind both goals are well tended grass banks; there is a scoreboard at the end that backs onto the carpark.

of steel supports. Behind both goals are well tended grass banks; there is a scoreboard at the end that backs onto the carpark. Sète in green and white hooped shirts with black shorts and socks, Stade Bordelais with black shirts with white shorts and socks. There is a ‘ceremonial’ kick-off before the real one, taken by a youmg woman with a green and white scarf draped around her shoulders. Eventually, referree Monsieur Guillaume Janin gives the signal for the game to start in earnest.

Sète in green and white hooped shirts with black shorts and socks, Stade Bordelais with black shirts with white shorts and socks. There is a ‘ceremonial’ kick-off before the real one, taken by a youmg woman with a green and white scarf draped around her shoulders. Eventually, referree Monsieur Guillaume Janin gives the signal for the game to start in earnest. man mountain with a wide shock of bleached hair on the top of his head, and thighs the size of other men’s waists.

man mountain with a wide shock of bleached hair on the top of his head, and thighs the size of other men’s waists.

which is close by at the corner of the stand where we are sat. The reason for my eagerness is that Sète is the home of the tielle, a small, spicy, calamari and tomato pie, with a bread like case. I love a tielle, and I love that they are specific to Sete, and are served at the football ground as a half-time snack. I only wish there were English clubs that served local delicacies. Middlesbrough has its parmo, but I can’t think of any others. Do Southend United serve jellied eels or plates of winkles? Do West Ham United serve pie and mash? Do Newcastle United serve stotties? Did the McDonald’s in Anfield’s Kop serve lobscouse in a bun? I need to know. Sadly, I don’t think my town Ipswich even has a local dish. Many English clubs don’t even serve a local beer; Greene King doesn’t count because it is a national chain with all the blandness that entails.

which is close by at the corner of the stand where we are sat. The reason for my eagerness is that Sète is the home of the tielle, a small, spicy, calamari and tomato pie, with a bread like case. I love a tielle, and I love that they are specific to Sete, and are served at the football ground as a half-time snack. I only wish there were English clubs that served local delicacies. Middlesbrough has its parmo, but I can’t think of any others. Do Southend United serve jellied eels or plates of winkles? Do West Ham United serve pie and mash? Do Newcastle United serve stotties? Did the McDonald’s in Anfield’s Kop serve lobscouse in a bun? I need to know. Sadly, I don’t think my town Ipswich even has a local dish. Many English clubs don’t even serve a local beer; Greene King doesn’t count because it is a national chain with all the blandness that entails.

minus crenellations. I swing the car round to park at an angle between the road and the high grey wall. We walk in the road past the ends of other parked cars to the main entrance to the stadium. There’s no one much about, just a few Dunkerque fans waiting around outside and they are outnumbered by the security people; hefty blokes in navy blue uniforms and one blonde and not at all hefty woman. The guichets (ticket booths), which look like arrows might be fired from them, are not open yet, but soon one does open and once the bearded man inside has finished his conversation with someone who remains invisible to us from the outside, I hand over €20 for two tickets, children are admitted free, but we haven’t brought any of those with us.

minus crenellations. I swing the car round to park at an angle between the road and the high grey wall. We walk in the road past the ends of other parked cars to the main entrance to the stadium. There’s no one much about, just a few Dunkerque fans waiting around outside and they are outnumbered by the security people; hefty blokes in navy blue uniforms and one blonde and not at all hefty woman. The guichets (ticket booths), which look like arrows might be fired from them, are not open yet, but soon one does open and once the bearded man inside has finished his conversation with someone who remains invisible to us from the outside, I hand over €20 for two tickets, children are admitted free, but we haven’t brought any of those with us. is the only stand, a tall steel and concrete structure with a steep pitched roof. There are eighteen stanchions (I counted them) evenly spaced along the stand supporting a network of struts that in turn support the roof. The other three sides of the ground consist of wide sweeping terraces

is the only stand, a tall steel and concrete structure with a steep pitched roof. There are eighteen stanchions (I counted them) evenly spaced along the stand supporting a network of struts that in turn support the roof. The other three sides of the ground consist of wide sweeping terraces

who turn and face the stand and wait a good five minutes for the teams to appear. Meanwhile the pitch sprinklers briefly come on, first in one half, then in the other, making the boys squirm and laugh as they get wet. The public address system stutters into life as the teams are announced in the style of a French Freddie ‘Parrot Face’ Davies. The small band of ultras, the Kop Biterrois

who turn and face the stand and wait a good five minutes for the teams to appear. Meanwhile the pitch sprinklers briefly come on, first in one half, then in the other, making the boys squirm and laugh as they get wet. The public address system stutters into life as the teams are announced in the style of a French Freddie ‘Parrot Face’ Davies. The small band of ultras, the Kop Biterrois , whose logo seems to be a monkey in a hat and sunglasses, are at the end of the stand and one of them beats a drum. After a minute’s silence the referee Monsieur Benjamin Lepaysant begins the match and AS Béziers kick -off towards the Cameron’s factory end of the ground. Straight from the kick- off we are treated to a cameo of how the match will pan out as Béziers indelicately boot the ball toward the Dunkerque goal, where the visiting full-back heads it weakly back to his goalkeeper, but it spins out comically for a corner to Béziers.

, whose logo seems to be a monkey in a hat and sunglasses, are at the end of the stand and one of them beats a drum. After a minute’s silence the referee Monsieur Benjamin Lepaysant begins the match and AS Béziers kick -off towards the Cameron’s factory end of the ground. Straight from the kick- off we are treated to a cameo of how the match will pan out as Béziers indelicately boot the ball toward the Dunkerque goal, where the visiting full-back heads it weakly back to his goalkeeper, but it spins out comically for a corner to Béziers. she has ever had the misfortune to visit. Worse than the North Stand toilets at Fratton Park back in the early 1970’s apparently, and no wash basin. A French girl refused to enter one cubicle. I hear the half-time scores from the other Ligue National matches over the echoing tannoy and I might be wrong, but it sounds like they are all nil-nil. I like to think they are.

she has ever had the misfortune to visit. Worse than the North Stand toilets at Fratton Park back in the early 1970’s apparently, and no wash basin. A French girl refused to enter one cubicle. I hear the half-time scores from the other Ligue National matches over the echoing tannoy and I might be wrong, but it sounds like they are all nil-nil. I like to think they are. where a man is sitting at a desk. I can only assume that this is the location for the Délègue Principal for this game, Monsieur Roger Lefebvre;

where a man is sitting at a desk. I can only assume that this is the location for the Délègue Principal for this game, Monsieur Roger Lefebvre; nevertheless, I cannot help imagining my vision zooming in on him whereupon he looks up and says “…and now for something completely different”.

nevertheless, I cannot help imagining my vision zooming in on him whereupon he looks up and says “…and now for something completely different”.

one, from Carcassonne; both shots are from angles, across the face of goal. Uchaud have an uncharacteristically solid, English looking centre half at number four, whilst as well as having a Julien Palmieri lookalike at number eleven, their number six bears a disturbing resemblance to former French international and alleged sex-tape starlet Matthieu Valbuena.

one, from Carcassonne; both shots are from angles, across the face of goal. Uchaud have an uncharacteristically solid, English looking centre half at number four, whilst as well as having a Julien Palmieri lookalike at number eleven, their number six bears a disturbing resemblance to former French international and alleged sex-tape starlet Matthieu Valbuena. attached with velcro; his shirt, shorts and socks all look brand new as if this is their first outing; he’s like an outsized boy on his first day at school. Carcassonne look the slightly more accomplished team and have more forays forward, but Uchaud are well organised and in Palmieri (who the rest of the team call Kevin), Valbuena and their captain they have three players who stand out for their skill and good positional sense; their goalkeeper contributes too with his constant calls of “parlez vous” (talk) and “garde” (keep it) as well as the odd catch from a cross. Carcassonne finish the half with a flourish winning the game’s first corner and then seeing their number three place a free-kick carefully over the angle of post and crossbar, before their dreadlocked number eleven runs in behind the Uchaud defence only to hit a low shot beyond the far post.

attached with velcro; his shirt, shorts and socks all look brand new as if this is their first outing; he’s like an outsized boy on his first day at school. Carcassonne look the slightly more accomplished team and have more forays forward, but Uchaud are well organised and in Palmieri (who the rest of the team call Kevin), Valbuena and their captain they have three players who stand out for their skill and good positional sense; their goalkeeper contributes too with his constant calls of “parlez vous” (talk) and “garde” (keep it) as well as the odd catch from a cross. Carcassonne finish the half with a flourish winning the game’s first corner and then seeing their number three place a free-kick carefully over the angle of post and crossbar, before their dreadlocked number eleven runs in behind the Uchaud defence only to hit a low shot beyond the far post.