When planning a long weekend trip to France, ostensibly to enjoy a Christmas market, it is important to ensure that there will also be a convenient football fixture to attend, there’s only so much mulled wine, churros and roast chestnuts that one can imbibe after all. So it is that with Amiens away to Laval and Lille in Marseille, I find myself with my wife Paulene in Reims (pronounced Rance but without really saying the ‘n’), city of Champagne, art deco architecture, Gothic splendour and the place where Clovis, the first king of what would become France, was baptised in about four ninety-seven. Coincidentally, in two night’s time this very same Clovis will be the answer to a question on University Challenge about which king was baptised in Reims in about four ninety-seven.

The dramatic concrete shapes of Stade Auguste Delaune, home of Stade de Reims are a twenty-five minute walk from our hotel according to Google maps. With kick off at 9pm local time we set off well before eight o’clock to allow for my wife’s short legs and asthma, and getting lost. The last time we went to a match in Reims we caught a tram, but that night our hotel was near a tram stop; tonight it’s not and it’s probably just as well because I don’t think the trams are running, something about an earlier “perturbation” (disturbance) and a “greve” (strike). It’s a marrow chillingly cold evening, so a walk will keep the circulation going, and it is warmer than it has been during the afternoon, when it rained; an hour away to the north there are reports of snow.

Two of the satisfyingly avant-garde, pointy floodlights of the Stade Auguste Delaune eventually hove into view like a seven or eight centuries late alternative to the Gothic spires that the magnificent cathedral of Notre-Dame de Reims was meant to have, but never did; cancelled like a medieval HS2. The whole stadium then appears before us as we reach the busy Boulevard Paul Doumer and cross over the Aisne-Marne canal and Voie Jean Tattinger, which run side by side. Eventually, we reach the stadium and the short queue to negotiate security who pat us down thoroughly. It is strange how at French football matches, despite much tighter security than in England, someone, and often several people, always seem to be able to sneak in some flares or smoke canisters.

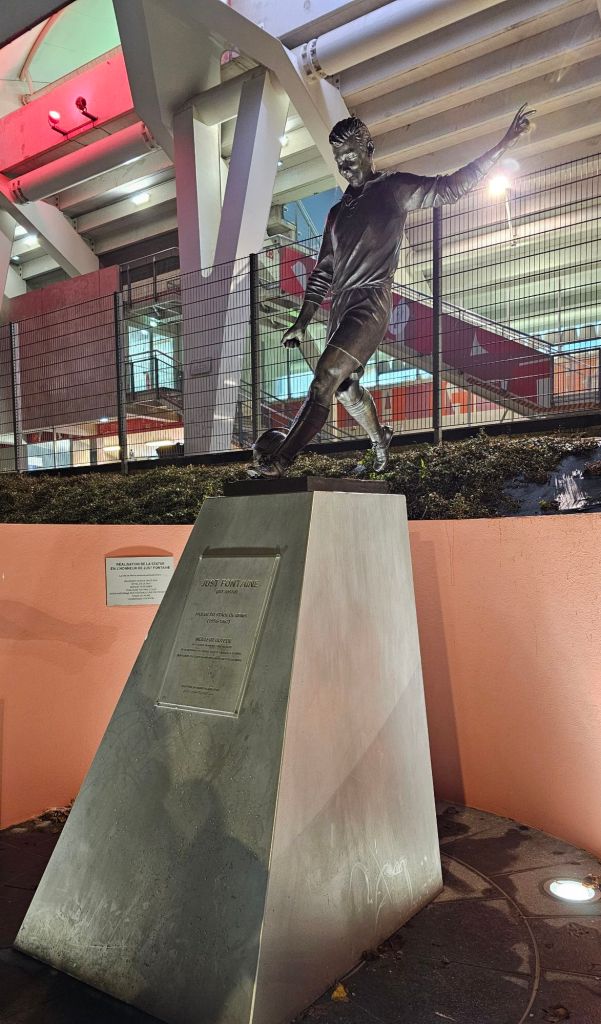

After a brief visit to the club boutique, where I decide 29.95 euros is too much for a T-shirt, we make our way to the other side of the stadium, past statues and murals of Raymond Kopa and Juste Fontaine, who were the French Ted Phillips and Ray Crawford in 1962, to the turnstiles and our seats (35 euros each) in the upper tier of the tribune Francis Meano. We take it in turns to use the facilities and as I wait for Paulene I stand and watch two men looking very pleased with themselves as they drink champagne and photograph themselves at the back of the stand. Sadly, I haven’t spotted any programmes, and with our tickets being on our phone I will have no memento of this game only memories, unless that is I rip my seat off its concrete base and hide it under my coat on the way out..

Stade Auguste Delaune is an exciting looking stadium, the work of architect Michel Remon. It was completed in 2008 and is on the site of the ground where the club has always played. Weirdly however, there is perhaps less to it than meets the eye, as it is skeletal with no enclosed landings or concourses, only the vaulted, cantilevered roofs over the four tribunes. In contrast to most similar sized English stadiums (21,684 capacity) however, it is a triumph of rakish angles, steps, curves and concrete, not a defeat to painted metal sheeting and tubular steel.

On arrival at the top of the final flight of stairs, we stand a moment to get our bearings and look about to try and spot our seats amongst the lettered rows. Immediately to our right sits a line of six men and women in late middle age and one much younger male; all of them are, not to put too fine a point on it, very fat. Like Michel Platini or Zinedine Zidane about to take a free-kick over a defensive wall into the top corner of the goal, our brains and eyes quickly and instinctively make a calculation and conclude that we will not be able to squeeze past these enormous people to our seats, and nor would we want to. Instead, we opt for a short free-kick, walking unopposed along the row behind, which fortuitously is completely vacant. We sit in the seats directly behind where we should be sitting and hope no one has bought them. As we await kick-off, we take in the sights and sounds of flashing floodlights and a bullish stadium announcer, who although annoying in almost every way imaginable, reads out the first names of the home team wonderfully, providing the perfect cues for the home crowd to bellow the players’ surnames; and what surnames they are, Agbadou, Atangana Edoa and Nakamura to name just three. Who wouldn’t enjoy shouting those out?

When the game begins it is Monaco who get first go with the ball, aiming it mostly in the direction of the goal to our left, which stands before the tribune Albert Batteux and the turnstiles through which we entered the stadium. Monaco wear an all bottle green kit, looking like and yet looking nothing like a more chromatically subdued Yeovil Town or Gorleston. Reims parade in their signature home kit of red shirts with white sleeves and shorts, like a sophisticated Rotherham United, albeit from a city steeped in Champagne and the historic coronation of French royalty rather than scrap metal.

To our right, behind the other goal, but confined to a corner are the Monaco fans, about 900 of them and they are in fine voice, chanting “Monagasque, Monagasque” and “Allez, Allez, Monaco” to the constant rhythm of a drum, the beater of which hardly ever looks up at the match, it’s as if he’s here in a wholly professional capacity, just to beat the drum. I like to think he’s on the payroll of Prince Albert, the Monagasque sovereign.

Since the game began, the seats to our right have become occupied, the three closest to us being a temporary home to three impossibly smart and neatly presented young people, a man and two women. The man sits between Paulene and the taller of the two women, who is dressed in white trousers over which she wears a long white fur coat; she probably spent more time applying her make-up and doing her hair than she’ll spend at the match. On the pitch, eleven quite dull minutes pass before the first shot of the game arrives, an effort which goes both wide of and above the goal. The shot is by the usually pretty reliable Aleksandr Golovin, a player who for some reason I consider to be a Dean Bowditch lookalike.

Golovin’s impressively inaccurate goal attempt will unexpectedly prove to be representative of the whole match and ten minutes later Monaco’s Eliesse Ben Seghir is through on goal but smashes a terrible shot over the cross bar. Seven minutes after that Monaco’s Takumi Minamino is all on his own in much the same position and succeeds in winning the game’s first corner. Although hopeless in front of goal, Monaco have been marginally the better side until Reims breakaway, win a corner and Marshall Munetsi glances a header over the Monaco cross bar. The Monaco supporters continue to chant and sing however, undeterred by a line of half a dozen stewards who cover some of the area in front of the stand , like a sort of human Maginot line, which would inevitably be easily breached if anyone made it onto the pitch.

The descent towards half-time brings the worst miss yet as Reims’ Keto Nakamura appears to be set up perfectly at the far post after a break down the right , only to despatch the ball in almost the completely the wrong direction in the manner of someone who has no idea what he is doing, or if he does, he doesn’t want to do it. Another type of entertainment is soon provided by Monaco’s extravagantly numbered Soungoutu Magassa (number 88, but still not the highest numbered player on the field) as he is pointlessly booked for tugging at Junya Ito before Ito himself joins the ranks of players intent on blazing the ball as high and wide of the goal as possible. With the final minute of the half and then added on time, Ben Seghir and Golovin shoot straight at Diouf the Reims goalkeeper and Reims ruin a promising looking break from defence with an awful cross.

Half-time comes as a welcome break from the frustrating performances on the pitch and the girl in white fur embarks on her own personal telephone photo shoot as she explores how, through pictures she can tell the world of social media that she is at a football match. In front of us the tubbiest people in the ground all up and leave, presumably for a re-fuel at the buvette; they are joined by another even larger , but younger woman from the row in front of them whose clothes fail to cover up a large expanse of what must be cold flesh where her top was meant to meet the top of her trousers. On the pitch, we are entertained by three people attempting to kick a football through holes in a sheet hung across the face of one of the goals. One of them fails to lift the ball off the ground in three attempts, but another scores one out of three, which everyone seems to agree is a decent effort.

At ten o’clock the football resumes and the Monaco fans unfurl a tifo which reads Daghe Munegu, which, if the Monagasque dialect is as similar to the Ligurian dialect as Wikipedia says it is, possibly means something like “Give it a chance”. Sadly, as to why this makes any sense as a slogan at a football match, I have no idea, but it all adds to the colour, even though on this occasion the words on the tifo are in black type on a white background. Back on the field of play, the pattern of the first half more or less continues as Ito runs down the wing, cuts inside and sets up Diakite to shoot against the cross bar for arguably the best shot of the game so far.

Monaco have improved on their first half display and win three corners in quickish succession as the first hour of the match slips away into history. Just to prove his increased commitment Kassoum Ouattara also gets himself booked. The increasing cold is penetrating deeper into our bones and Paulene puts a blanket over her knees whilst the seats directly behind us are filled by teenagers who all seem to be supporting Monaco, as does the young woman in the white fur, who has begun squealing excitedly when Soungoutu Magassa gets anywhere near the ball. In front of us, the weight watchers on a night out have returned to their seats and have colonised the places that are really ours, with buttocks straddling two seats at a time. Monaco are the first to make substitutions, perhaps as the team of whom more is expected because they sit second in the Ligue 1 league table to Reims’s middling ninth.

The final twenty minutes witness a Reims corner which is headed away, but otherwise it is Monaco who come closest, but never particularly close to scoring. Minamino gets past a defender only to shoot wide, substitute Elio Matazo scoops a shot over the bar and Ben Seghir shoots high too. But it’s all grist for the Monaco fans who happily sing “Na Na, Nana, Naa, Naa, Wey hey hey, Monaco” to the tune of the 1969 single “Na na, Hey hey, Kiss him goodbye” by the made-up band Steam. In the final ten minutes Henrique and Minamino add to the catalogue of missed goal attempts for Monaco and in time added on play ebbs back and forth in vain, whilst the young woman in the white furs, and her friend continue to yelp and shriek. The final whistle confirms what had become increasingly likely, that neither team would score. As we go to leave, the young man raises his eyebrows and possibly almost rolls his eyes. I’m not sure if his gesture is made in reference to the game or his accomplices, or all three.

The walk back to the hotel will prove to be long, cold and gently uphill, and there still won’t be any trams. As enjoyable as tonight has been tomorrow evening I think we’ll go back to the mulled wine, churros and roast chestnuts.