One of the many wonderful things about supporting a football team that is in the third division is that the FA Cup begins at the beginning of November. None of this inexorable waiting about for Advent, Christmas and then New Year to come and go. No siree, the joy of knockout football comes early to the meek who do more than just inherit the Earth, they get to chase the glory that is knockout competition football. Of course, we have already missed out on six rounds of extra-preliminary, preliminary, and qualifying rounds, but we can’t have everything and being meek we wouldn’t want it.

Today, the transparent plastic tub that serves as the 21st century’s replacement for the Football Association’s velvet bag has paired Ipswich Town with fourth division Oldham Athletic. This is a pairing to rival some of the worst failures ever, like a race between a Ford Edsel and a Sinclair C5, or a competition between the Enron bank and ITV digital. Ipswich Town and Oldham Athletic, I have been told, are the least successful clubs in English professional football in the past twenty years, being the only two who have either not been promoted or not made it to any sort of match at the new Wembley Stadium. The good thing is that this has saved us supporters a considerable amount of money on grossly over-priced tickets, match day programmes and catering, for which we should be grateful.

It’s a blustery, cloudy day and fallen leaves scuttle along the footpath as I make my way through Gippeswyk Park; the autumnal scene reminds me of some of the opening sequences of the film The Exorcist. Portman Road is very quiet, stewards in huge fluorescent orange coats, and sniffer dogs easily out number supporters outside the away fans’ entrance. The display on the windows at the back of the Cobbold Stand tell of former FA Cup glories and the day in March 1975 when a record crowd of 38,010 filled Portman Road to see the sixth-round tie versus Leeds United. I look at my watch, it’s a quarter to two; I had already been inside the ground nearly twenty minutes by now on that day forty-six and a half years ago. I buy a programme for a knockdown price (£2.00), and confirm to myself that I prefer this 32 page programme to the usual 68 page one, even though it costs more per page; I live in hope of an eight or twelve page edition for less than a pound.

At the Arboretum pub (currently known as the Arbour House), I choose a pint of Nethergate Augustinian Amber Ale (£3.80). The bar is unusually full, so my pint and I decant to the safety of the beer garden, which is reassuringly more like a backyard with tables and chairs. I text Mick to tell him “Je suis dans le jardin”. It’s not long before he joins me with a pint of beer and a cup of dry roasted peanuts. We talk of Ipswich Town, of property development and pension funds, catching the TGV to Marseille, the buildings of Le Corbusier, the colour theory of Wassily Kandinsky and the Bauhaus, and electric cars. A little after twenty-five to three we leave for Portman Road, bidding the barmaid goodbye as Mick places our empty glasses and the cup that no longer contains peanuts on the bar.

Our tickets today (£10 for me, £5 for Mick plus £1.50 each unavoidable donation to some parasitic organisation called Seatgeek) are for Block Y of what is now known as the Magnus Group Stand, but used to be the plain old West Stand, named simply after the compass point rather than a commercial concern called West that had paid for the privilege. Flight upon flight of stairs take us to the dimly lit upper tier of the stand where we edge past a line of sour-faced males of indeterminate age, but over fifty, to our seats. My guess is there won’t be much banging of drums, lighting of flares or even vocal encouragement from these people, who look more like Jesuit priests than football supporters.

Although Remembrance Sunday isn’t until next week, and there will be a minute’s silence before the game versus Oxford United next Saturday, bizarrely we have another pre-match minute’s silence today. Stadium announcer Stephen Foster tells us it is because we are in the ‘Remembrance period’ but it feels like football just likes minutes silences. As ever the silence is strangely followed by applause, and then the game begins. For the first forty-five minutes Town will be mostly trying to send the ball in the direction of the goal in front of the Sir Alf Ramsey stand (previously known as Churchman’s end) where in the lower tier I can make out ever-present Phil who never misses a game and Pat from Clacton. Later, Mick will ask me if “the lady from Essex” still comes to the games, and I will point her out to him, locating her using gangways and rows of seats like co-ordinates in a game of Battleships. Mick spots her and Pat from Clacton is sunk. Oldham Athletic are wearing a fetching ensemble of orange shirts and black shorts with orange socks; it’s a kit that stirs memories of Town’s fifth round tie away at Bristol Rovers in the snow of February 1978; or it would if, as is the modern fashion, Oldham’s shirts didn’t look like they’d had something spilled down the front of them.

Town start the game well with Oldham’s interestingly named Dylan Fage conceding a corner within the first minute before the oddly named Macauley Bonne heads a cross directly at goalkeeper Jayson Leutwiler. Within eight minutes Town lead as the oddly named Macauley Bonne’s cross sees Wes Burns do an impression of the shopkeeper in Mr Benn as suddenly, as if by magic he appears to score from very close range. This is just the start we need; we will now surely go on to win by three or four goals to nil because Oldham Athletic are third from bottom of the fourth division and Town won 4-1 at Wycombe Wanderers on Tuesday, what more convincing evidence predicting our inevitable victory could there be? Indeed, Town continue to look the better team as the oddly named Macauley Bonne and Wes Burns both have shots blocked, but then the shots become fewer to be replaced by scores of passes back and forwards across the pitch.

Bersant Celina tries a little flick pass with the outside of his right foot, which doesn’t succeed. “You’ve got to earn the right to do that sort of thing” announces the joyless sounding man beside me to the World, presumably unaware that he is talking rubbish; you just need to get it right. Oldham break forward and are a pass away from a shot on goal on a couple of occasions. “We’re leaving the door open” continues the joyless man, seemingly happy to be miserable.

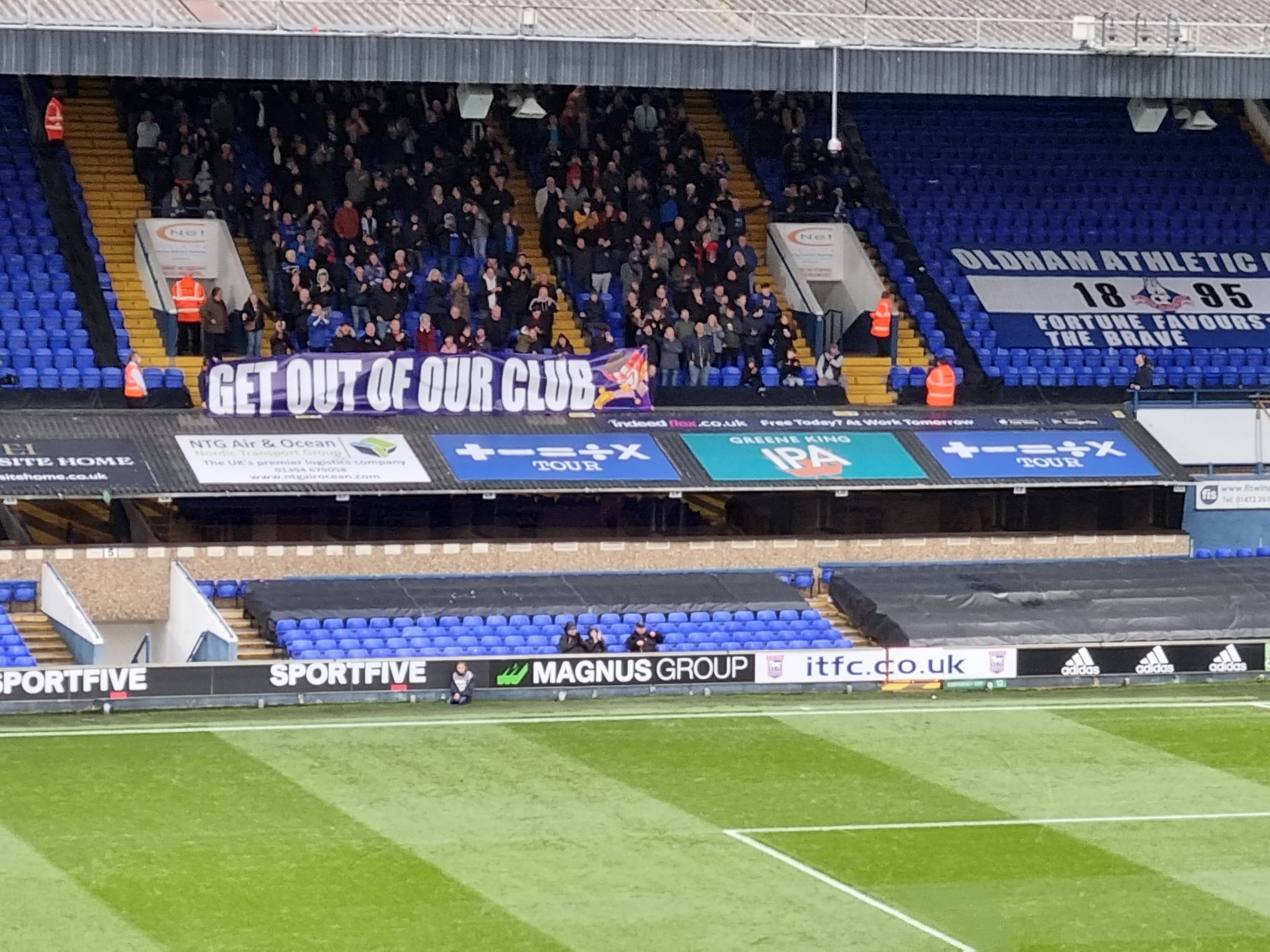

Despite the 1-0 lead, the Portman Road crowd, which will later be announced as consisting of 437 Oldham supporters within a paltry total of 8,845, is quiet. Where are the other 29,165 who were here in 1975? A good number are probably no longer alive, I guess. “Your support, your support, your support is fucking shit” chant the Oldham supporters in the Cobbold stand with predictable coarseness. I feel like telling them that’s because some of us are dead. Despite high hopes the FA Cup seems to have lost a little of its sparkle and it’s only twenty -five past three. I realise that over the Cobbold Stand and across the roof tops beyond I can see the top of the Buttermarket shopping centre. It’s the twenty seventh minute and Oldham’s number nine, the optimistic sounding Hallam Hope heads the ball just wide of the Town goal.

Seven more unremarkable minutes pass and the sometimes not very controlled Sam Morsy is booked by referee Mr Hair, who it is to be hoped will one day referee in the Bundesliga. Stupidly, having dropped to the ground under a challenge, Morsy grabs hold of the ball as if to award himself a free-kick. Rightfully, Herr Hair books him for hand ball and the pointlessness of the incident mirrors the drifting aimlessness of the Town performance and its quiet backdrop; this isn’t what Cup football is meant to be like.

After a couple of further failed goal attempts from Oldham, with four minutes left until half-time they score. Latics’ number ten, Davis Keillor-Dunn, who sounds like he could have been friends with Lytton Strachey and Virginia Woolf, sends a fine shot into the corner of the Town goal from about 20 metres after Toto Nsiala initially fails to deal with a ball that had been booted forward. “How shit must you be we’re drawing 1-1” sing the Oldham supporters to the tune of Sloop John B, coincidentally showing the majestic timelessness of the Beach Boys’ 1966 album, Pet Sounds.

With half-time fast approaching Kane Vincent-Young tugs an Oldham shirt to concede a free-kick. “Stupid boy” says a man who sounds even more joyless than the man next to me but nothing like Captain Mainwaring in Dad’s Army. I suggest to Mick that players should have their hands bound with tape to prevent them from pulling each other’s shirts; ever reasonable and practical Mick suggests they simply wear mittens. Following a corner to Oldham, the half ends and with the exception of one man, the occupants of Row J rise and then descend the stairs to use the toilets and the catering, or to just stand about.

As Mick and I wait for the queue to the toilet to shorten we talk of exorcism, the disappointment of the first half, the architectural splendour of the Corporation tram shed and power station in Constantine Road, and how my wife Paulene has a degree in theology. I decide I can wait until after the game for a pee and whilst Mick joins the queue and disappears into the toilet, I am impressed by the long hair of a man standing a few metres away from me, but die a little inside when I read in the programme that when he grows up one of today’s mascots wants to be a policeman. More happily, the other two mascots want to be a footballer and a superhero.

Back in our seats the second half begins with the unusual replacement of both Ipswich full-backs as Janoi Donacien and Steve Penney replace Kane Vincent-Young and Cameron Burgess. It’s a change that brings almost immediate results as a mittenless Janoi Donacien tugs an orange shirt and Herr Hair awards a penalty to Oldham. The otherwise impressive Dylan Bahamboula steps up for Oldham to see his penalty kick saved by Christian Walton and a sudden roar fills Portman Road which belies the small number of people present. For a few minutes the home crowd is energised and it physically feels as if we care as much we think do. Wes Burns dashes down the wing, urged on by the crowd, but the sudden excitement is evidently too much and he propels his cross way beyond the far post and away for a goal kick. “How much more waking up do we need?” asks the joyless soul next to me.

To an extent Town’s performance in the second half is better than that of the first. The full-backs now on the pitch are an improvement on those they replaced and Oldham produce fewer decent chances to score. When Connor Chaplin replaces the ineffective Kyle Edwards the link between Morsy and the front players is strengthened and another dimension is added to our attacking play, but somehow it’s still not enough. As I tell Mick, all our players look like they got home at four o’clock this morning.

As Town’s failure to score grows roots and blossoms, the Oldham supporters gain in confidence. “Come on Oldham, Come on Oldham” they chant, giving a clue to the home fans as to what they might be doing, but we don’t twig. The upshot with ten minutes to go is a reprise of that old favourite “Your support, your support, your support is fucking shit” and who can argue, it’s no longer 1975. Despite Oldham encouraging Town with a misplaced pass out of defence, we are unable to capitalise and the Oldham supporters are the only ones singing as they ask “Shall we sing, shall we sing, shall we sing a song for you?” Predictably no one dares break our vow of silence to answer their question.

As the game enters its final minutes Sone Aluko replaces our best player, Wes Burns, and Rekeem Harper replaces Lee Evans. Encouragingly Oldham replace their best player, Dylan Bahamboula with Harry Vaughan, but nothing works and five minutes of added on time only raises hopes, but does not fulfil them.

The final whistle is blown by Herr Hair and the crowd get up from their seats showing the same level of emotion that they might if they were all on a bus and it had just reached their stop, turning away from the pitch and averting their gaze like you would if trying to avoid eye contact with a drunk. It has been a very disappointing afternoon of FA Cup football, and has failed on every level to live up to what the competition is supposed to be about.

On the bright side, at least we are still in the draw for the Second Round and until we lose, the promise of glory still remains. It’s not every year we do as well as this.

near the Atlantic coast, some 380 kilometres away by road; they have won one and lost two of their four games so far. Kick-off is at six pm and we arrive about a half an hour beforehand, parking in the spacious gravel topped car park at the side of the Stade Louis Michel, although other spectators prefer to park in the road outside. Entry to the stadium costs €6 and we buy our tickets from the aptly porthole-shaped guichets

near the Atlantic coast, some 380 kilometres away by road; they have won one and lost two of their four games so far. Kick-off is at six pm and we arrive about a half an hour beforehand, parking in the spacious gravel topped car park at the side of the Stade Louis Michel, although other spectators prefer to park in the road outside. Entry to the stadium costs €6 and we buy our tickets from the aptly porthole-shaped guichets  outside the one gate into the ground. Just inside the gate a cardboard box propped on a chair provides a supply of the free eight-page, A4 sized programme ‘La Journal des Verts et Blancs’. Also today there is a separate team photo and fixture list on offer.

outside the one gate into the ground. Just inside the gate a cardboard box propped on a chair provides a supply of the free eight-page, A4 sized programme ‘La Journal des Verts et Blancs’. Also today there is a separate team photo and fixture list on offer. the brutal angular concrete of the main stand, the Tribune Presidentielle, could be from the 1960’s or 1970’s, channeling the inspiration perhaps of Auguste Perret or even Le Corbusier. The concrete panels on the back of the stand are lightly decorated and sit above wide windows; a pair of curving staircases run up to the first floor around the main entrance,

the brutal angular concrete of the main stand, the Tribune Presidentielle, could be from the 1960’s or 1970’s, channeling the inspiration perhaps of Auguste Perret or even Le Corbusier. The concrete panels on the back of the stand are lightly decorated and sit above wide windows; a pair of curving staircases run up to the first floor around the main entrance,  above which is a fret-cut dolphin, the symbol of the town and the club. The stand runs perhaps half the length of the pitch either side of the halfway line and holds about twelve hundred spectators, as well as club offices and changing rooms. Opposite the main stand a large bank of open,

above which is a fret-cut dolphin, the symbol of the town and the club. The stand runs perhaps half the length of the pitch either side of the halfway line and holds about twelve hundred spectators, as well as club offices and changing rooms. Opposite the main stand a large bank of open,  ‘temporary’ seating runs the length of the pitch, it is built up on an intricate lattice

‘temporary’ seating runs the length of the pitch, it is built up on an intricate lattice  of steel supports. Behind both goals are well tended grass banks; there is a scoreboard at the end that backs onto the carpark.

of steel supports. Behind both goals are well tended grass banks; there is a scoreboard at the end that backs onto the carpark. Sète in green and white hooped shirts with black shorts and socks, Stade Bordelais with black shirts with white shorts and socks. There is a ‘ceremonial’ kick-off before the real one, taken by a youmg woman with a green and white scarf draped around her shoulders. Eventually, referree Monsieur Guillaume Janin gives the signal for the game to start in earnest.

Sète in green and white hooped shirts with black shorts and socks, Stade Bordelais with black shirts with white shorts and socks. There is a ‘ceremonial’ kick-off before the real one, taken by a youmg woman with a green and white scarf draped around her shoulders. Eventually, referree Monsieur Guillaume Janin gives the signal for the game to start in earnest. man mountain with a wide shock of bleached hair on the top of his head, and thighs the size of other men’s waists.

man mountain with a wide shock of bleached hair on the top of his head, and thighs the size of other men’s waists.

which is close by at the corner of the stand where we are sat. The reason for my eagerness is that Sète is the home of the tielle, a small, spicy, calamari and tomato pie, with a bread like case. I love a tielle, and I love that they are specific to Sete, and are served at the football ground as a half-time snack. I only wish there were English clubs that served local delicacies. Middlesbrough has its parmo, but I can’t think of any others. Do Southend United serve jellied eels or plates of winkles? Do West Ham United serve pie and mash? Do Newcastle United serve stotties? Did the McDonald’s in Anfield’s Kop serve lobscouse in a bun? I need to know. Sadly, I don’t think my town Ipswich even has a local dish. Many English clubs don’t even serve a local beer; Greene King doesn’t count because it is a national chain with all the blandness that entails.

which is close by at the corner of the stand where we are sat. The reason for my eagerness is that Sète is the home of the tielle, a small, spicy, calamari and tomato pie, with a bread like case. I love a tielle, and I love that they are specific to Sete, and are served at the football ground as a half-time snack. I only wish there were English clubs that served local delicacies. Middlesbrough has its parmo, but I can’t think of any others. Do Southend United serve jellied eels or plates of winkles? Do West Ham United serve pie and mash? Do Newcastle United serve stotties? Did the McDonald’s in Anfield’s Kop serve lobscouse in a bun? I need to know. Sadly, I don’t think my town Ipswich even has a local dish. Many English clubs don’t even serve a local beer; Greene King doesn’t count because it is a national chain with all the blandness that entails.