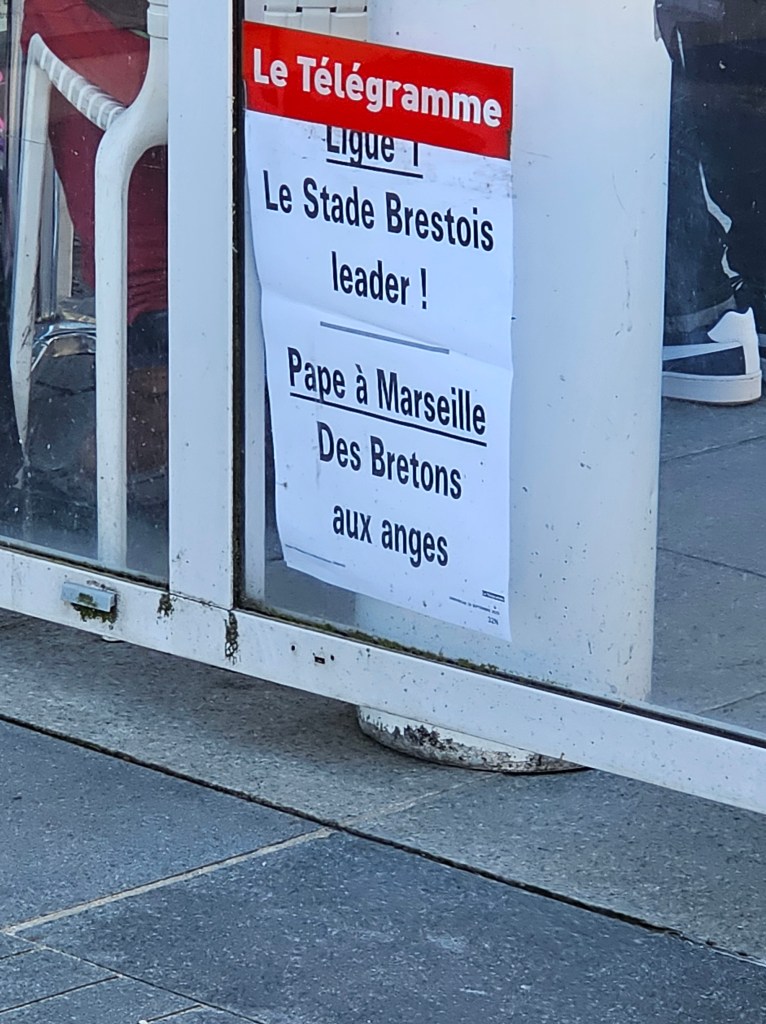

Finistere is the most westerly departement or ‘county’ of metropolitan France, with its name translating pretty much as ’the end of the earth’. Not far east of the most westerly point of the most westerly department is Finistere’s largest town, Brest, an historic port and naval city, which was almost totally flattened by allied bombing during World War Two because the Nazis occupied it and made it part of their strategic ‘Atlantic Wall’. Today, having been rebuilt in the 1950’s with an emphasis on space and layout rather than impressive or pretty architecture, although the church of St Louis de Brest is a notable exception, Brest has a population a little larger than that of Ipswich, but serves a metropolitan area of twice as many people, and is home to Stade Brestois 29, a football club in their present incarnation now enjoying their longest spell in the French first division since the 1960’s. Tonight, Stade Brestois who are currently third in the first division table, play Olympique Lyonnais who are third from bottom and I will be there. A win for Brest will put them top of the league above OGC Nice who won 1-0 away to previous leaders AS Monaco last night.

My wife Paulene and I are staying in a city centre hotel, which proves very handy indeed for the Liberte tram stop, where I just manage to extract two tickets (€1.70 each) from the vending machine and jump aboard a bright lime green Ligne A tram before it shuts its doors and begins a gentle, whirring, electricity-drinking ascent up Rue Jean Jaures towards Place de Strasbourg, from where it is just a short walk along Rue de Quimper to Stade de Francois Ble, home of Stade Brestois 29 (the 29 is the number of the Finistere departement – for some reason the mainland departements are numbered from 1 to 100, although weirdly Corsica gets to be 2A and 2B). A gathering crowd is plainly in motion as we alight from the tram, and there is no difficulty finding the stadium as we are consumed by the human tide being drawn by the glow of floodlights shining out through the Breton dusk, and the promise of beer from the bar immediately behind the ground. There is something about the approach to the ground and its relationship to the street that reminds me of the old Dell in Southampton, but I don’t let it worry me and not seeing any indication of a club shop I follow Paulene into the stadium after the usual ‘patting down’ by a huge, friendly man of Franco-African origin, who ensures I am not smuggling flares or other unfashionable trousers into the stadium.

My fears about being unable to source club merchandise are quickly allayed as I spot a small wooden hut which looks like it could double up for use at a Christmas market. I‘ve done my homework on-line, and know that for a bargain €9.90 I might be able to obtain a T-shirt bearing the club crest and the slogan Marree Rouge (Red Tide). I point at a box of red T-shirts which bear the markings described and ask if there is one in ‘Large’ size. The helpful young woman searches, examining the labels in collar after collar, one by one, but without success. Eventually, sensing my desperation she holds up XL and XXL shirts as if suspecting that I am the sort of bloke who looks capable of putting on several kilos in weight if it suddenly proves necessary. Optimistically, believing that I can fool the world by holding my stomach in, I ask if there is not a medium sized shirt instead; there is, but then, as she delves into the cardboard box just one more time a miracle happens, and she pulls out a ‘Large’; very possibly the last one in existence that isn’t already being worn by a well-proportioned Breton.

Clutching my precious T-shirt, I head for stairway five of the Tribune Foucauld and having climbed three flights of concrete steps I find myself looking over the brilliant green, floodlit pitch; all that remains is a further climb to row X and our seats, which I bought on-line a couple of weeks back. Stade Brestois operate a loathsome ‘dynamic’ pricing system in which the club acts like a tout and the price of a seat changes, according to how much they think they can get for it. When I first looked, tickets were €80 each; I eventually scored two of the few remaining ones for €45. The club says the system means that people playing top price for seats allows less well-off fans to get cheap seats, but presumably this is only if these poorer fans have nothing to do with their time but be permanently logged onto the club website, waiting for a ticket price they might be able to afford. The stadium has a capacity of not many more than 15,000 and is almost full for every Ligue 1 game. We sit in our over-priced seats and enjoy the view, which includes, through fading light, sight of the wide inlet from the Atlantic Ocean, which gives Brest its advantage as a port and naval dockyard. Opposite us, the Tribune Credit Mutuel Arkea has five thick tubular stanchions set at a rakish angle to hold up the roof; atop the stanchions and the roof are floodlights, although the ground also has lights in all four corners. To our right is the open Tribune Atlantique, a metal temporary stand a la Gillingham, and it’s where the away supporters are inevitably penned into a corner, they don’t even get seats, just metal benches. Behind the stand, the occupants of a block of flats get a free view and can be seen crowding around windows and Juliet balconies. To the left is the small but freshly renovated Tribune Quimper; the ‘home end’ where the majority of the Brest Ultras congregate.

Whilst Paulene stays put to get maximum value from her seat, I soon take a wander to see what I can see and to find a programme, which is as ever free, and tonight is of the newspaper variety; it tells me the squads and who the referee and linesmen are and that’s it, which is all I need to know. On the mezzanine level one staircase down from our seats is a bar, above which is a banner advertising the Breton Lancelot brewery. Expecting one of Lancelot’s tasty beers, I invest 5 euros. The beer is sweet and nasty and probably non-alcoholic; I tell the barmaid so and ask if it is Lancelot, because it doesn’t taste like it. She doesn’t know but thinks it’s probably Carlsberg. I’ve been poisoned. At either ends of the stand are what look like private members bars, “Le Caban” and “L’esprit des Legendes”. Spectators entering these bars do so only after having received the nod from people dressed intimidatingly all in black; presumably that’s where they serve the good stuff. I’m guessing those spectators aren’t in the cheap seats.

I return to my seat, and in the company of Paulene time passes quickly as we watch Zif, Brest’s pirate mascot, parade before the stand, and enjoy the arrival of the people in the seats around us, most of whom seem to be blokes in their seventies who all know each other. The man next to me wears a beret and seems very clean, like Paul McCartney’s grandad in A Hard Day’s Night, but French. When the teams at last come onto the pitch, it’s to the fanfare of the Ligue 1 ‘anthem’, leaping flames, and the presentation of the match ball on a shiny plinth in front of banners displaying the two club badges and the Ligue 1 logo. The public address system seems loud enough to make my ears bleed, but happily it doesn’t, although I do check.

When the game begins it is Lyon, generally known as OL in France, who get first go with the ball which they try and aim in the direction of the ocean whenever they can. OL wear a frankly hideous, and annoyingly unnecessary away kit of all blue with red trim, whilst Brest are in their signature red shirts with white shorts and red socks. It’s been a warm day, but now a strong breeze blows up the hill from the dockyard and towards the OL goal. From the start, the slogan on my recently purchased T-shirt proves accurate as Brest sweep forward with wave after wave of attacking intent. A shot goes way, way over the Lyon goal and then another soon earns a corner. Brest are easily the better team but can’t find the final pass or the final touch that counts. In midfield for Brest, Pierre Lees-Melou is brilliant, despite having previously played for Norwich City, and I imagine that the Canaries simply had no idea how to integrate a player into their team who can pass accurately, tackle, shoot, run with the ball and generally be quite good. Fortunately, Lees-Melou seems to have suffered no ill-effects from his thirty-odd games wearing yellow and green., but he’s probably receiving counselling.

All around the ground, the crowd brays with indignant disapproval whenever a Brest player is fouled. When referee Thomas Leonard books OL’s Ernest Nuamah for fouling Lees-Melou, the cheers sound like a goal has been scored. I enjoy the wonderful name of Kenny Lala for Brest and the terrible haircut of Maxence Caqueret of Lyon, a player who looks like he was born 120 years too late and should have been the singer in a 1930’s dance band. On twenty-four minutes Lees-Melou has a shot tipped onto the cross bar by OL goalkeeper, the excellent Anthony Lopes, and then Brest’s Jeremy Le Douaran curls the rebound around the angle of the post and the bar. “Allez-Allez-Allez” chant the home crowd from every stand. A minute later OL get the ball into the Brest penalty area for the first time, but it comes to nought and instead all around is the noise of Brest fans urging their team on to score the goal the balance of play says they deserve. The Ultras in the Tribune Quimper call out and the rest of the stadium answers back. Mahdi Camara, a recent signing from Montpellier, dribbles deep into the OL box but again, there is no goal, only anticipation and excitement. In the corner of the open end, the OL fans seem oblivious to their team’s ineffectiveness, other than in defence, and have sung and chanted all through the first half, prompted by two blokes perched astride the high metal fence that separates the supporters from the pitch. Both blokes wield loud halers, but I don’t know if it’s the effect of the strong on shore breeze blowing away most of the sounds of their voices, but they both sound like Rob Brydon’s small man trapped in a box.

The fortieth minute is a milestone in the game as OL win their first corner, but of course it doesn’t result in a goal, and it’s the Brest supporters who remain in ebullient mood, holding their scarves aloft in the Tribune Quimper as the first half draws to a close in a sort of 1970’s tribute that suits the architecture of the stadium and the old blokes all around me who were themselves probably the Ultras of fifty years ago. In front of me, a bloke wears double denim, and succeeds in accentuating the feeling, as if he’d come to a game in 1973 and never went home.

With half-time, the seats to our left are nearly all vacated, revealing the fact that they all sport red covers and suggesting perhaps that their occupants are now all enjoying some form of hospitality somewhere, perhaps in Le Caban or L’Esprit des Legendes. I will read later that the club owners wish to build a new stadium at the end of the tram line at the edge of the city, but that it will still only have a capacity of 15,000, no doubt because they want to be able to still charge top prices for the comfortable few and forget about the sweaty oiks who may be don’t wear shirts, and chant and light flares and drink too much beer containing alcohol in the bar across the road.

The second half begins and nothing changes, although encouragingly the block of seats to our left is soon re-populated, proving either that the occupants are genuinely interested in the match or that the hospitality isn’t free or unlimited. After just seven minutes however, OL roll the dice by replacing Ernest Nuamah, Diego Moreira and Paul Akounkou with Mama Balde, Tino Kadeware and Ainsley Naitland-Miles, who tonight wears a silly number 98 shirt and a few seasons ago mostly failed to excite when on loan at Ipswich from Arsenal. The change sort of works for a short while and Alexandre Lacazette finds space to launch a thirty-yarder which flies over the Brest cross bar, but then a weak Caqueret pass is intercepted by Lees-Melou who dribbles away from his own half and to the edge of the OL penalty area before frustratingly shooting beyond the far post. An hour has gone and Brest miss another chance, probably the best yet, as a low cross is somehow steered wide of the OL goal by Jeremy Douaron from just a couple of yards. Whilst clutching their collective heads the crowds shout “Aye-Aye-Aye” and I find myself joining in with swelling chants of “Allez les Rouges! Allez les Rouges!” Paulene, a Pompey fans says the atmosphere is like that of Fratton Park. “The same sort of people” she says. “What? All dockyard mateys” I reply, thinking of my dead father, a one-time Pompey based matelot who I know would have said exactly the same thing.

The game enters its final twenty minutes, and to mark the occasion tonight’s attendance is announced as being 14,636, and Brest substitute number seven, Martin Satriano for number nine, Steve Mounie. But it’s OL who, still against the run of play, now come closest to a goal as Lacazette sends a decent low shot goalwards from the edge of the penalty area which Brest ‘keeper Marco Bizot dives to his right to stop and then jealously grab. Lacazette lasts five minutes more before being replaced by Rayan Cherki, a man whose distinctly bushy facial hair and short back and sides give him the look of an Edwardian naval captain.

Three minutes of normal time now remain. A move down the right produces a cross from Brest’s Kenny Lala, which Steve Mounie heads against the foot of Lopes’s left hand post. As the crowd gasps in thrilled disappointment the ball runs back to Lala who crosses it again and Mounie, who has back-pedalled judiciously, this time hurls himself forward to head the ball past Lopes into the near top corner of the net, and Brest have the goal they deserve. The crowd is on its feet, but OL defender Tino Kadewere is on the ground having been barged out of the way by the hurtling Mounie, although there was no real suspicion of a foul.

“Allez, Allez, Allez, Allez” we all sing triumphantly, Billal Brahimi shoots, Lopes saves, and Brest have a corner and five minutes of added on time in which to retain their clean sheet or even score again. The very clean old bloke in the beret, next to me, leaves early, but very few others do. Jonas Martin shoots and misses for Brest, and Naitland-Miles has a shot saved for OL, but there are no more goals and as the clock ticks towards eleven o’clock Monsieur Leonard blows his whistle for the last time. Brest are top of the league, or more accurately given our geography, a la tete du classement. We stay a short while to applaud before heading off into the night and back along Rue de Quimper to the tram stop, and a journey back to our hotel on the most crowded tram I have ever ridden on. It’s been a fantastic evening and still with our minds whirring excitedly, in our hotel room we celebrate Brest’s success by cracking open a small bottle of Cremant that had been cooling in the mini-bar, and unwind by watching the game all over again on Canal Plus tv. Allez les Rouges!