One of the best things about visiting France in September is being able to catch a game in the early rounds of the Coupe de France when the competition is still regionally based and there are ample opportunities to see village teams slug it out in quest of the sort of glory only village teams can enjoy.

Having arrived in Brittany just yesterday, after an overnight stop in Le Mans, I can’t be bothered to travel far from where my wife Paulene and I are staying in Carnac, added to which it’s a grey, miserable day and when if it’s not full-on raining there is a steady drizzle as if the Atlantic Ocean is stealthily relocating itself slightly inland. After consulting the list of fixtures on the Ligue Bretagne de Foot website I have whittled the possibilities down to US Brec’h v Av.Campeneac-Augan or ASC Saint Anne d’Auray v Avenir Guiscriff. Both are between twenty and twenty-five minutes away by planet saving Citroen e-C4 but St Anne-d’Auray ASC have a grass pitch as opposed to a plastic one, and taking a chance on the rain having not caused a postponement I decide that I would rather see people getting muddy than getting friction burns, and so I head for St Anne d’Auray.

St Anne-d’Auray is a curious place, a village with a population of less than 3,000 people but also the location of the third most visited pilgrimage site in France after Lourdes and Lisieux, as a result of which, and also because of which, it also has a huge basilica. Wikipedia tells us that St Anne-d’Auray became a site of pilgrimage after a pious farmer in the early 17th century kept having persistent visions of St Anne, who somewhat weirdly told him to rebuild a chapel which had been demolished about 900 years previously. The farmer must have been a sort of renaissance era Nigel Farage figure as people were evidently keen to believe his unlikely tales, the chapel was built, and by the 1870’s had become the present basilica.

As a I drive into St Anne d’Auray along the D17, through the early afternoon gloom the tower of the basilica looms above the roof tops wreathed in low cloud. A left turn takes me down the Rue de General de Gaulle and to the Stade Municipal where luck shines upon me and a car is leaving the otherwise full car park just as I arrive. I park up and step out of my planet saving electric Citroen, and my nostrils are assaulted by the acrid smell of barbecue smoke. I saunter through the gates to the Stade Municipal in my long navy-blue raincoat and join the throng of local inhabitants socialising, drinking and generally enjoying themselves in a sort of impromptu ‘fanzone’ where everybody seems to know everyone else. Entry to the match is free of charge with the football club clearly being content with the income from beer, wine, coffee and food.

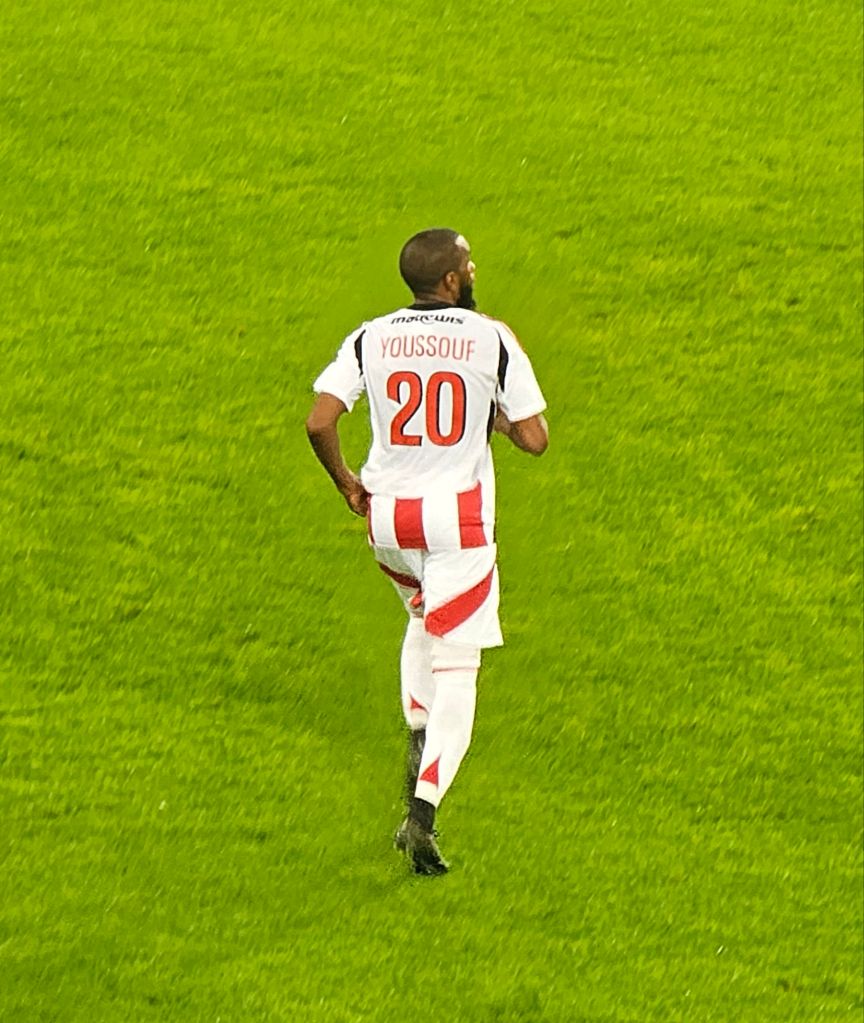

Kick-off is advertised as being at three o’clock but it’s nine minutes past by the time the two teams emerge from the dressing rooms and trudge their way to the pitch behind the referee and his assistants, the clumping of their metal boot studs on the tarmac sounding like a marching army and the basilica providing a suitably religious back drop for a Sunday afternoon. The tarmac driveway passes through a gap in an impressive row of tall oak trees that line the east side of the stade, which has no stand, just a tarmac path all around and a metal rail surrounding the pitch. After photos and the usual cursory handshakes, the teams line up and after an initial ‘ceremonial’ kick off by a bearded and balding man, it is visiting Guiscriff AV who get first go with the ball, sending it mostly in the rough direction of the nearby town of Auray, whilst the home team shoot towards the basilica. St Anne d’Auray wear a kit of red shirts and black shorts whilst Guiscriff are adorned in all navy blue with gold or beige chevron on their chests.

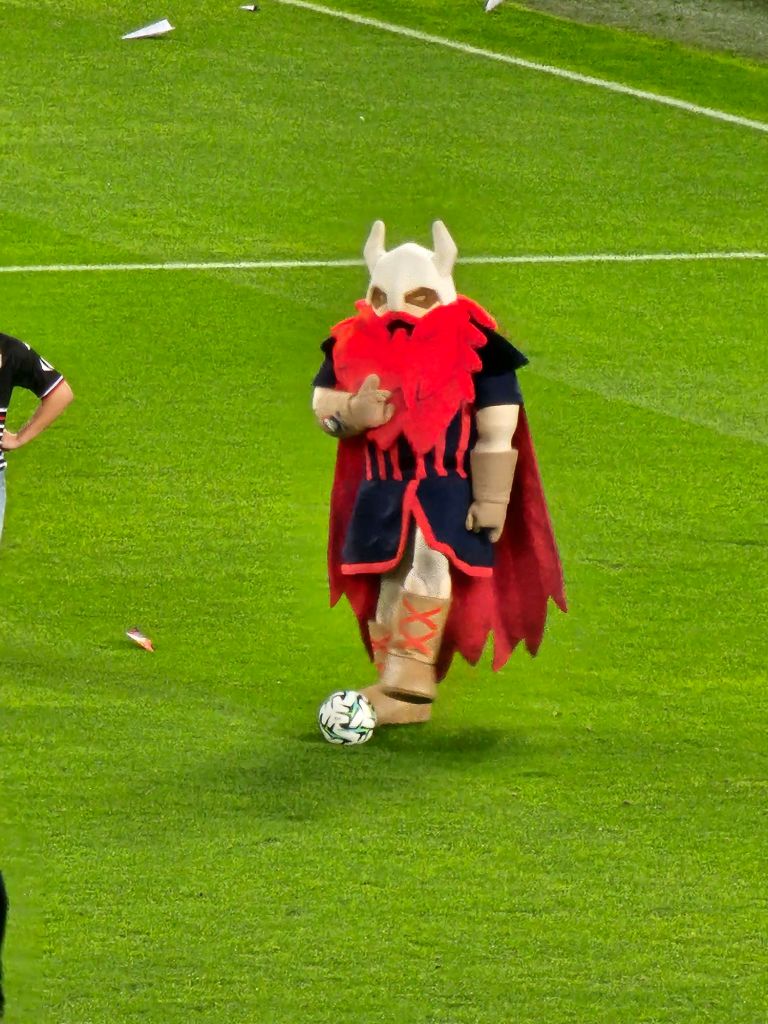

The crowd of at least two hundred is enthusiastic and congregates on each side of the pitch behind the well-maintained metal rail. Guiscriff is a village 84 kilometres away to the northwest near Quimper, is about an hour and ten minutes’ drive away, and a good number of visiting supporters have travelled, including a man carrying a blue, cuddly, toy rabbit, which I assume is some sort of mascot, but he could just be a friend or comfort. The stadium has no flood lights but although it’s a grey afternoon, it’s not so grey that these are going to be needed.

Just two minutes pass and a cute through ball down the left from the Guiscriff number nine sends their number eleven away into the penalty area where he comfortably slips the ball past the St Anne d’Auray goalkeeper to give the away team a very early lead. After the excitement of the start of the match and the teams marching to the pitch, the home supporters now appear as religious followers whose tenets of faith have suddenly all been disproved. But whilst 84km apart geographically, the two sides are at the same level in the regional league, so all is by no means lost just yet, although when the bells of the basilica start to toll the sound is somewhat ominous. The away supporters meanwhile are delirious and having visions of the fourth round.

Happily, the shock of going behind is soon processed mentally and the noisiest home supporters assembled opposite the team dugouts are quickly in good voice again with chants of “Aux Armes”. An adversarial atmosphere is stoked as there are enough away supporters to render a few decent chants of “Allez les bleus” too. On the pitch, the balding number five and number eight for St Anne d’Auray appear influential but Guiscriff are holding firm quite comfortably, with the home team’s forays forward mostly foundering on slippery grass, offsides and shoves and pushes that the referee (l’arbitre en Francais) Monsieur Romain Betrom spots but the home supporters don’t.

It’s now twenty-two minutes past three and it’s beginning to look like St Anne will struggle to reverse the early deficit but then almost miraculously there’s a careless trip and Monsieur Betrom is pointing to the penalty spot. After a long lecture from Monsieur Betrom and eventually a yellow card (carton jaune) for Guiscriff’s number five, who I can only think postulated an alternative view of events a little too vigorously, the rangy number ten for St Anne d’Auray steps up to score, a good two minutes after the penalty kick had first been awarded.

With the scores level the whole match begins to even out and Guiscriff no longer look the better team. At twenty-five to four St Anne d’Auray win a free kick, which ends up in the back of the Guiscriff net courtesy of one of their own player’s boots, but Monsieur Betrom disallows the ‘goal’ for pushing, shoving, holding, blocking or a combination of the four. There was certainly a lot going on in the penalty area with fouls likely being committed by both sides; Monsieur Betrom clearly took the view that if in doubt just pretend the whole incident never happened and leave the score as it is, and who can blame him?

I wander around the ground taking the game in from different angles and enjoying the grey afternoon scene against the backdrop of oak trees and the tower of the basilica beyond. Briefly I stand close to the village ‘ultras’, who are mostly teenagers but are well equipped with banners, two empty oil drums for percussion and a loud hailer. Not long after I settle against the rail just beyond the bulk of the more boisterous home support, Monsieur Betrom makes a decision that will probably define the match, as he shows his carton rouge (red card) to the St Anne d’Auray number eleven. There is an inevitable delay as this is discussed but eventually number eleven makes his way towards the gap in the tall oak trees and back to the changing rooms.

Inevitably Monsieur Betrom’s decision is not a wholly popular one and there is much braying amongst the home crowd. I exchange raised eyebrows with a middle-aged man a metre or two away along the rail and then move next to him when he speaks to me. Happily, the extent of his English and my French seem vaguely complimentary, and in a somewhat stilted way we are able to discuss the Coupe de France, the match and Monsieur Betrom, the man even does an impression of Donald Trump. Half-time (mi-temps) arrives and is accompanied by a sudden increase in precipitation, so I turn up the collar on my coat. The man, who I will later learn is called Frederique invites me to join him and his friend Patrick at the bar. He jokingly suggests we can talk about Brexit, which I suspect he feels as disappointed about as I do. At the bar, Patrick very kindly buys me a beer, and Frederique introduces me to several other people including the local mayor a small, kindly looking man with a big moustache, and another friend, Jean Baptiste.

When the football resumes, I stand near the dugouts with Frederique and Patrick and try to avoid the rain, which is now coming straight at us, from getting into my beer. The match continues in much the same vein as it did in the first half and Guiscriff seem incapable of making any advantage of their extra player. The Guiscriff coach strides up and down the touchline seemingly talking to himself but possibly cursing his players. When his goalkeeper concedes a free kick by picking up a back pass, he almost has a seizure. Monsieur Betrom meanwhile, a thin, gaunt looking man much younger than his two assistants, one of whom has grey hair, spends much of his time brandishing his carton jaune. For every one of the many bookings he delivers he stands to attention, with his card holding arm at 45 degrees, a pose he holds for a full two or three seconds as if at some sort of Nuremburg rally for referees.

“Carton rouge!” shouts Frederique for as many fouls as he thinks he can, which amuses a short elderly couple stood next to me, and then “Allez l’arbitre!”. The game proceeds through the continuing gloom although happily the rain stops falling. Substitutions are made, but no resolution seems in sight until suddenly by way of another miracle there is an ill-judged, attempted tackle on the edge of the St Anne d’Auray penalty area, and for the second time this afternoon monsieur Betrom points to the penalty spot. The penalty is scored and with less than ten minutes left to play Guiscriff are once again heading for round four.

No more than five minutes later, Guiscriff lead 3-1 after a sequence of a corner, a shot and a deflection concludes with ball nestling once more in the back of the St Anne d’Auray goal net. It’s a disappointing end to the afternoon for St Anne d’Auray and matters get slightly worse when there is a contretemps between a local and a man in a Guiscriff sports coat. Glaring looks are exchanged, beer is spilt and the game stops as the matter is discussed by the referee, one of his assistants and a man wearing an armband who I assume is the delegue principal, a sort of fourth official. “Just football” says Frederique philosophically.

With the final whistle, the celebrations from the Guiscriff players and supporters are ecstatic, winning a Coupe de France tie means a lot. With Frederique, Patrick and Jean-Baptiste I turn away and head for the gap between the tall oaks. Frederique asks if I am coming back to the bar with them, but reluctantly I must turn down their invitation as my wife Paulene is waiting for me back in Carnac.

Despite the rain, the gloom and the disappointing result for the home team it’s been another wonderful afternoon in the Coupe de France, and my love for this competition and all things French has just received another layer of gloss, although I’ve not learned anything new except perhaps that St Anne was possibly not a football fan, but given that she was supposedly the Virgin Mary’s mum, I never thought she was.