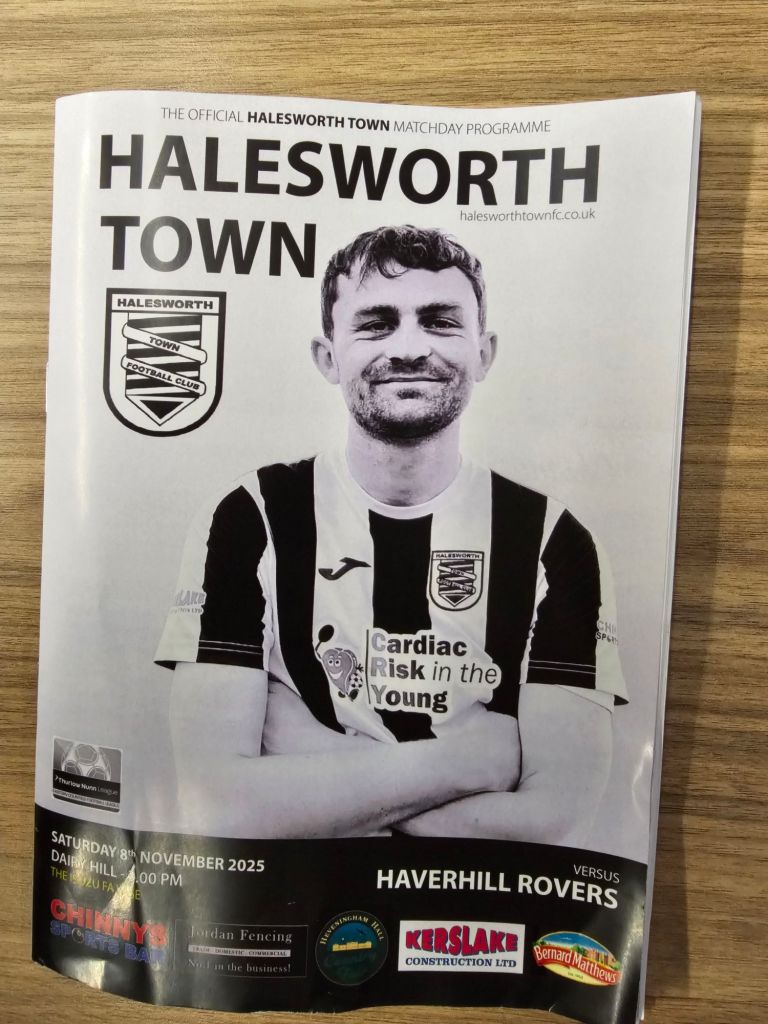

Between March 2017 and April 2019, I watched matches at each one of Suffolk’s then twenty-four senior football clubs and recounted my experiences in this here blog. Since then, Debenham Leisure Centre and Whitton United have sadly dropped out of senior football but this season the Eastern Counties League First Division North has welcomed two more Suffolk clubs into the fold in the shape of Kings Park Rangers, who are from Great Cornard but seemingly too shy to admit it, and Halesworth Town, who are proudly, clearly from Halesworth.

Today, with Ipswich Town playing far too far away in deepest Wales to trouble me to even think of getting a ticket, even if I had enough ‘points,’ I am travelling up to Halesworth in part one of my plan to restore my record of having seen all of Suffolk’s senior teams on their home turf. Fortuitously, today’s fixture is also an all-Suffolk cup-tie against Haverhill Rovers of the Eastern Counties Premier League, and the first time Halesworth Town have ever reached the second round of the FA Vase. To add to the adventure even more, despite the additional twenty minutes each way that it will take me, I am responsibly reducing congestion on the roads by eschewing making the 88-kilometre journey from my home by planet saving Citroen e-C4 in favour of taking the train (£18.10 return with senior railcard). It also means I can get plastered if I choose to.

It’s an intermittently cloudy but mild November day as I set off for Halesworth, but I am nevertheless surprised as I wait for the train that one of my fellow travellers appears to have forgotten to put on any trousers or a skirt. Once on the train, the infinite variety of human life continues to reveal itself as a small man of pensionable age repeats the names of the station stops as they are heard over the public address system; every now and then he delves headfirst into a large carrier bag as if checking on the wellbeing of a small animal or perhaps a baby. When the woman sitting opposite me goes to the buffet car, she asks me to mind her belongings. I of course agree but tell her she needs to be back before we get to Ipswich. When she returns, I tell her I had to fight off a couple of people who looked interested in her jacket but otherwise everything has been fine. Fortunately, she laughs, but the man of east Asian origin next to me looks at me askance and when she begins to struggle to open a bottle of drink, he very quickly offers to help so that she doesn’t have to deal with the looney opposite her again. The woman soon begins to chew on a large sandwich and a younger man on the other side of the aisle between the seats does the same thing, but takes much bigger bites, happily from a different sandwich, although with every bite he looks like he might lose a finger.

I change trains at Ipswich, boarding the 13:16 to Lowestoft, which departs a good twelve seconds early. I like the East Suffolk line, to me it feels like a one-hundred- and seventy-year-old umbilical cord connecting the outside world to rural Suffolk with its rustic sounding stations such as Campsea Ashe and Darsham and their Victorian architecture. Between the stations are Suffolk landscapes of river and marsh, Oak and Broom, sheep and pigs, outwash sands and boulder clay and gaunt, grey, flint church towers. As the guard checks passengers’ tickets, he helpfully advises those alighting at Halesworth not to use the doors in the front carriage, because the Halesworth station platform is not that long. There seem to be quite a few of us alighting at Halesworth.

The train arrives on time in Halesworth, where the sun shines from a pale blue autumn sky. A helpful sign points and tells pedestrians that it’s a seven-minute walk to the town centre and a minute’s walk to local bus stops on Norwich Road. Sadly however, no sign points helpfully towards Halesworth Town football ground, although having previously consulted the interweb I happen to know it is very close indeed, perhaps no more than a hefty goal-kick away. I walk up an alley between the railway lines and Halesworth Police station, a huge four-storey block of a building, which although it probably dates from the1960’s makes me think of a Norman castle keep, built to keep the locals in check. At the top of the alley, I turn right over a bridge above the railway and then right again down another alley the other side of the tracks, and down to the Ipswich bound railway platform. From here it is no more than 150 metres up Dairy Hill to the football ground, making it a toss-up between Halesworth and Newmarket as to which senior Suffolk football ground is most easily accessible by rail, my money’s on Halesworth.

Despite its attractive name, Dairy Hill is just an uninspiring street of modest modern houses; from the top I make my way across the stony club car park and along the back of the club house to the ground entrance. For a mere seven pounds I gain a programme (£1.00) and entry to the match as an over sixty-five, all that is missing is the click of a turnstile. The ground itself is underwhelming, but it does boast a decent looking pitch with a smart timber fence all around and a small stand at the end nearest the clubhouse, which according to ground grading rules needs to be big enough to accommodate fifty spectators, although I’m not sure if FA rules say how large or small the spectators need to be. The height of Halesworth’s stand suggests they should not be significantly taller than about 1.8 metres unless wearing crash helmets.

I head for the club house where the bar offers the usual array of fizzy lagers and cider and a pump which intriguingly bears the name ‘Wainwright’ written in biro on a plain white sticky label. The barman generously allows me a sampler of the ‘Wainwright’ and seeing as there’s nothing-else I might like I order a pint (£4.60) before heading outside again to visit the food trailer, where a tall man with tattooed arms, who looks like men in food trailers often do serves me chilli, chips and cheese for a modest six pounds, less than half what I paid for much the same thing in an Ipswich pub earlier this week.

I return to the club house to eat my chips and drink my beer, not being someone who likes to eat or drink standing up. The club house looks like there might be an older timber building, which has had a new roof and supporting structure placed over the top of it, it smells a little like that too, having a faint musty odour which isn’t uncommon in old village halls and clubhouses. The black and white interior décor and monochrome photos of old teams on the walls remind me a little of the Long Melford club house before it was re-built.

With chips eaten and beer drunk, I wait outside for kick-off, observing the growing crowd and the queue to get in at the gate, before standing closer to where the two teams will line up before the procession on to the pitch to shake hands and then observe the minute’s silence for remembrance day, a silence which whilst well observed around the pitch plays out to a back ground of chatter from inside the bar and clubhouse, where life continues as usual, oblivious to the silence outside.

Eventually, it is Haverhill Rovers who begin the game, by getting first go with the ball, which they quickly hoof forward in the general direction of the stand, the railway station and town centre beyond, before it is booted into touch by a Halesworth defender, not unreasonably practicing safety first. It’s good to see both teams wearing their signature kits, Rovers in a rich shade of all red, whilst Halesworth sport black and white stripes with black shorts. In front of the only stand, a youth bangs the sort of drum I wouldn’t bet against him having been given as a present for his sixth birthday, probably about six years ago. The bulk of the crowd are lined up behind the post and rail fence along the touchline opposite the dug outs and when Halesworth win the ball they emit an encouraging rustic roar.

Seven minutes have passed and it’s Rovers who are the team kicking the ball most of the time; their number seven Prince Mutswunguma performs a neat turn and a decent cross which is headed over the Halesworth cross bar. The pattern of the game is generally one where the long ball is favoured over short passes and two minutes later Mutswunguma blazes the ball high above the Halesworth cross bar. I stroll along the front of the empty stand between it and the pre-pubescent ultras but remain nervous of hitting my head on the low roof. I stop close to the corner flag, halted by a sign forbidding further progress and disappointingly preventing me from walking round to watch the game from behind or between the dugouts, where the angst and frequent bad language of the managers and coaches is often as entertaining as the match. I am nevertheless now in a good position to see Rovers’ desperate claims for a penalty as Mutswunguma tumbles under a challenge from number 6, Ollie Allen and then two more players fall over. “Fucking disgraceful” opines a gruff voice from somewhere, either on the pitch or in the dugouts, but I’m not sure if he means not giving a penalty or having the temerity to appeal for one.

Keen to see the game from as many angles as possible I move again, this time to near the corner flag diagonally opposite the one I have been standing by. I settle near a man in late middle age who sports a Stranglers t-shirt and beanie hat bearing the name of The Rezillos, the excellent late 1970’s Scottish ‘punk’ band fronted by Faye Fife and Eugene Reynolds. He is on his mobile phone and seems to be arranging a claim on his motor insurance having hit something when parking his car in the club car park. In my new position I also benefit from a good view of an increasing number of unsuccessful Halesworth breakaways as the home team gain in confidence from repelling all Rovers’ attempts to score.

In goal for Halesworth, George Macrae has made a string of fine saves as Rovers win a succession of corners. Rovers’ best effort is a shot from Kyle Markwell, whose surname gives a clue to the opposition as to how to treat him, that whistles past a post. A half an hour is lost to history and Halesworth fashion another breakaway as captain Toby Payne receives a diagonal pass out on the left. “He’s on! He’s on! Well, he’s not off” shouts a young man to my left with rising excitement as Rovers’ offside trap is sprung. Payne advances into the penalty box, shapes up to shoot but then side foots weakly too close to the goalkeeper Alex Archer, who doesn’t have to stretch far to prevent a goal. Two minutes later however Halesworth break again down the left and this time the ball is pulled back from the by-line for Lewis Chenery to score easily into the middle of the Rovers’ goal from no more than 8 metres out and it’s 1-0 to Halesworth Town.

The remaining dozen minutes of the half repeat the established pattern of the previous thirty-three, and another Rovers’ corner is headed wide, which I view from back near the clubhouse as I prepare to be ahead of the queues for the toilet and the tea bar when the referee, the extravagantly monikered Mr Gasson-Cox sounds the half-time whistle. Having invested in a pound’s worth of tea I take-up a position for the second half just to the right of the stand, but not before I overhear a club official talking to the man on the gate and learn that the attendance today is a stonking two-hundred and fifty-eight. As the new half begins and the light fades, the lovely smell of the turf rises up from the pitch. A woman standing next to me tells me we will see the goals at this end in the second half and I agree, telling her that with the goal being scored at the other end in the first half, it figures that this is the end where the goals will be scored this half. We talk a little more and after I reveal I have an Ipswich Town season ticket, she admits to being a Norwich City supporter, but sympathetically I tell her someone has to be.

With the start of the second half at three minutes past four Halesworth seem to have lost a little of the confidence they showed by the end of the first half, perhaps because they realise they have to go through another forty-five minutes similar to the first, and indeed they do. But with twenty minutes gone and no further score it is Rovers who first feel the need to make substitutions. “Who are ya?” chant the pre-pubescent ultras, as well they might as the new players emerge from the dugout. Five minutes later and Halesworth’s Tane Backhouse is the first player to see the yellow one of Mr Gasson-Cox’s two cards, although as I become increasingly biased in favour of the home team and their superb goalkeeper, I can’t really figure out why. Two minutes later and I’m cheering as another characteristic break down the right sees Toby Payne run to the edge of the Rovers penalty area, cut across a little towards the middle and then shoot unerringly inside the far post and Halesworth lead 2-0. “Oh when the Town go marching in” sing the mini ultras, as do a number of people old enough to know better, but understandably carried away by the moment.

Things get no better for Rovers as after an innocuous looking foul Mr Gasson-Cox nevertheless seems annoyed with Prince Mutswunguma and standing his ground, summons him over before showing him the yellow card. “Wemberley, Wemberley” sing the Halesworth fans who should know better but are now too happy to care, but as they do so Rovers, perhaps realising their desperate position with only ten minutes left embark on a final push. It’s twenty to five as George Macrae makes another fine save, this time diving low to his left. “Two-nil down on your big day out” sing the pre-pubescents, not helping the situation with their cruel taunts and Rovers win another corner. The corner is cleared but moments later the ball is crossed low from the right and Rovers’ number eleven and captain Jarid Robson half volleys it high into the centre of the goal from a narrow angle and the score is a nerve-wracking 2-1.

It’s now eleven minutes to five, the match is a minute into added on time and Rovers are besieging the Halesworth goal like local Saxons or Danes outside the Norman police station. A cross comes in from the left, and a Rovers head goes up diverting the ball goalwards but once again George Macrae appears, seemingly from nowhere to save the day again by cleanly catching the ball. “Six more minutes Haverhill” I hear a voice call, perhaps from the Rovers’ dugout, or perhaps it was Mr Gasson-Cox or someone just mucking about. Six minutes seems an awfully long time given that neither I nor the lady next to me can recall anyone really being injured. Another Rovers corner goes straight to the arms of Macrae but then Halesworth break away again, bearing down on goal on the right and then switching the ball across the edge of the penalty box before number eleven Alex Husband shoots from a narrow angle and the ball strikes a Rovers defender and arcs up over Archer the goalkeeper and into the goal off the far post. It’s 3-1 to Halesworth! The game is surely won and the knot of Halesworth players hugging by the corner flag and the under12’s ultras who have run along behind us hoping to celebrate with them clearly think so.

Very soon however, it’s three minutes to five and finally Mr Gasson-Cox parps his whistle for the last time today and Halesworth are into the third round of the FA Vase. Most people wait to cheer and applaud the team as they leave the pitch, but not before they applaud Mr Gasson-Cox the referee and his assistants, which is something you don’t see every day, and then the Haverhill players too. It’s been a wonderful afternoon, an exciting cup-tie played in front of a large and appreciative crowd, and everyone’s had a lovely time. As I leave the ground and make my way back across the stony car park and down Dairy Hill to the station I reflect on what a fine little town Halesworth is and how one day I really should return. All hail Halesworth!